Body seen in Libyan mortuary could solve 50-year mystery of vanished religious leader

BBC

BBCWarning: Contains images some may find upsetting

A computer scientist at a university in the north of England is studying an image of a corpse – attempting to solve a mystery that has gripped the Middle East for nearly 50 years.

“This is what he looks like now?” asks Bradford University’s Prof Hassan Ugail doubtfully.

The digitised photo is of a decomposed face and it is about to be run through a special algorithm for our BBC investigation.

The original photo was taken by a journalist who saw the body in a secret mortuary in the Libyan capital in 2011. He was told then that it could be charismatic cleric Musa al-Sadr, who vanished in Libya in 1978.

Sadr’s disappearance has spawned endless conspiracy theories. Some people believe he was killed, while others claim he is still alive and being held somewhere in Libya.

For his ardent followers, his disappearance holds the same level of intrigue as the 1963 killing of US President John F Kennedy. Such is the sensitivity of our long investigation that my BBC World Service team and I even found ourselves detained in Libya for several days.

Emotions run high because Sadr is so revered by his followers – both for his political reputation, having advocated on behalf of his native Lebanon’s then-marginalised Shia Muslims, and as a wider religious leader.

His followers gave him the title of imam, an unusual honour for a living Shia cleric and one bestowed on him in recognition of his work on behalf of the Shia community.

His mysterious disappearance has added to his emotional power because it echoes the fate – according to the largest branch of Shia Islam, known as Twelvers – of the “hidden” 12th imam, who disappeared in the 9th Century. Twelver Muslims believe the 12th imam did not die and will return at the end of time to bring justice to Earth.

And Sadr’s disappearance also arguably changed the fate of the world’s most politically, religiously and ethnically volatile region – the Middle East. Some believe the Iranian-Lebanese cleric was on the verge of using his influence to take Iran – and, as a result, the region – in a more moderate direction when he disappeared on the eve of the Iranian revolution.

So there was a lot riding on Bradford University’s identification efforts. The journalist who took the photo told us the body was unusually tall – and Sadr was said to be 1.98m (6ft 5in). But the face had barely any identifiable features.

Could we finally solve the mystery?

Imam Sadr Foundation

Imam Sadr FoundationI am from the village of Yammouneh, high in the mountains of Lebanon, where stories have long been told of the terrible winter of 1968 when, after the community was devastated by an avalanche, Musa al-Sadr waded through deep snow to come to the village’s aid.

The wonder with which the villagers share this story today reflects just how mythologised he has become. One told me, referring to his memories as a four-year-old: “It was like a dream… He walked across the snow, followed by all the villagers… I followed him just to touch the Imam’s robe.”

Back in 1968, Sadr wasn’t well known in an isolated village like Yammouneh, but he was slowly garnering a national reputation. By the end of that decade he had become a major figure in Lebanon, known for advocating for interfaith dialogue and national unity.

His status was reflected in the honorary title “imam” bestowed on him by his followers. In 1974, Sadr launched the Movement of the Deprived, a social and political organisation which called for proportional representation for the Shia and social and economic emancipation for the poor, regardless of their religion. So determined was he to avoid sectarianism that he even gave sermons in Christian churches.

Imam Sadr Foundation

Imam Sadr FoundationOn 25 August 1978, Sadr flew to Libya, invited to meet the country’s then leader Colonel Muammar Gaddafi.

Three years earlier, Lebanon had erupted into civil war. Palestinian fighters became involved in the sectarian conflict, with many based in Lebanon’s south, where most of Sadr’s followers lived. The Palestinians had begun exchanging fire with Israel across the border, and Sadr wanted Gaddafi, who supported the Palestinians, to intervene to keep Lebanon’s civilians safe.

On 31 August, after six days spent waiting for a meeting with Gaddafi, Sadr was seen being driven away from a Tripoli hotel in a Libyan government car.

He was never seen again.

Gaddafi’s security forces later claimed he had left for Rome, though this was proved false by the investigations that followed.

Independent journalism was impossible in Gaddafi’s Libya. But in 2011, when Libyans rose against him during the Arab Spring, the door of probity opened a crack.

Kassem Hamadé, a Lebanese-Swedish reporter who covered the uprising, was told about a secret mortuary in Tripoli that, a source had said, might contain the remains of Sadr.

There were 17 bodies refrigerated in the room he was shown – one was of a child, the rest were all adult men. Kassem was told the bodies had been dead for about three decades – which would fit with Sadr’s timeline. Only one corpse resembled Sadr.

Kassem told me: “This one drawer, [the mortuary staff member] opens it, he reveals the corpse, and two things struck me immediately.”

Firstly, Kassem said, the look of the body’s face, skin colour and hair still resembled Sadr’s, despite the passage of time.

And secondly, he said, the person had been executed.

Or at least that was Kassem’s assumption, based on the skull. It looked as if it had either suffered a heavy blow to the forehead or been pierced by a bullet above the left eye.

But how could we know for sure this was Sadr?

Kassem Hamadé

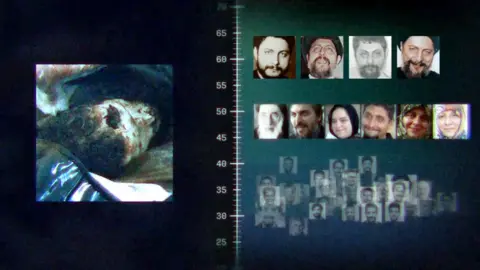

Kassem HamadéSo we took the photo that Kassem had taken in the mortuary to a team at Bradford University which, for the past 20 years, has been developing a unique algorithm called Deep Face Recognition. It identifies complex similarities between photos, and has been shown to be extremely reliable in tests, even on imperfect images.

Prof Ugail, who leads the team, agreed to compare the image from the mortuary with four photos of Sadr at different stages of his life. The software would then give the mortuary image an overall score out of 100 – the higher the number, the more likely it was to be either the same person, or a family member.

If the image scored below 50, the person was probably unrelated to Sadr. Between 60 and 70 meant it was him or a close relative. Seventy or higher would be a direct match.

The photo scored in the 60s – a “high probability” it was Sadr, Prof Ugail told us.

To test this conclusion, the professor used his same algorithm to compare the photo with six members of Sadr’s family, and then with 100 random images of Middle Eastern men who all resembled him in some way.

The family photos scored much better than the random faces. But the best result remained the comparison between the mortuary image and the images of Sadr alive.

It showed there was a strong probability that Kassem had seen Sadr’s body. And the fact he found it with a damaged skull suggested that, in all probability, Sadr had been killed.

In March 2023, some four years after I first came across Kassem’s photo, we were able to travel to Libya to talk to possible witnesses and to look for the body ourselves. We had always known the story was sensitive but even so, we were surprised by the Libyan reaction.

We were on the second day of our deployment in Tripoli, looking for the secret mortuary. Kassem, who was accompanying the BBC team, couldn’t remember the name of the area he had visited in 2011, except that it had been near a hospital.

We were told there was a hospital within walking distance and headed off to find it.

Suddenly, Kassem said: “This is it. I’m sure of it. This is the building that contained the morgue.”

The building’s exterior was the last thing we were able to film. We sought permission to film inside, but our permits were cancelled. The next day, a group of unidentified men – who we would later learn were Libya intelligence service officers – seized us without explanation.

We were taken to a prison run by Libyan intelligence, where we were held in solitary confinement, and accused of spying. We were blindfolded, repeatedly interrogated, and told that no-one could help us. Our captors said we would be there for decades.

We spent a traumatic six days in detention. Finally, after pressure from the BBC and the UK government, we were released and deported.

It was disturbing to feel we had become part of the story. Libya is still divided into two rival administrations with competing militia, and staff at the prison had indicated Libyan intelligence was being run by former Gaddafi loyalists who would not want the BBC investigating Sadr’s disappearance.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSome people have long believed Sadr was murdered.

Dr Hussein Kenaan, formerly a Lebanese academic working in the US, says he visited the State Department in Washington the week Sadr disappeared in 1978 and was told it had received a report that he had been killed.

This account is backed up by the former Libyan Minister of Justice, Mustafa Abdel Jalil, who told Kassem in 2011: “The second or third day, they forged his papers, that he’s going to Italy. And they killed him inside Libyan prisons.”

He added: “Gaddafi has the first and the last word in all decisions.”

So if Gaddafi did order Sadr’s killing, then why?

One theory, says Iran expert Andrew Cooper, is that Gaddafi was influenced by Iranian hardliners, alarmed that Sadr was about to obstruct their objectives for the Iranian Revolution.

Sadr supported many Iranian revolutionaries who wanted an end to then-ruler Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s regime. But his moderate vision of Iran strongly differed from the ideas of Islamic hardline revolutionaries and was disliked and even resented by them.

A week before his disappearance, according to Cooper, Sadr had written to the Shah offering assistance.

Cooper interviewed Parviz Sabeti, a former director of counter espionage for the Shah’s secret police, as part of his research for a biography of the Shah. Sabeti told him that Sadr’s letter offered to help defuse the power of Islamic hardliners by working towards introducing policy changes that would appeal to more moderate elements of the opposition.

A former Lebanese ambassador to Iran confirms the existence of Sadr’s letter. Khalil al-Khalil told us he understands it requested a meeting with the Shah scheduled for 7 September 1978.

Cooper believes this information was leaked to Iranian hardline revolutionaries.

But the Iranians are not the only people who might have wanted Sadr dead.

Gaddafi had been militarily supporting Palestinian fighters attacking Israel from southern Lebanon – and Sadr is quoted in interviews from the time explaining his attempts to find a solution with the Palestine Liberation Organisation [PLO].

The PLO may have believed Sadr, fearing they were endangering the Lebanese population, might have convinced Gaddafi to rein them in.

While there are many who believe Sadr to be dead, others are adamant he is still alive.

These include the organisation Sadr founded in the 1970s, now a powerful political party of the Lebanese Shia called Amal.

The head of Amal – and parliamentary Speaker – Nabih Berri, maintains there is no proof Sadr, who would now be 97, has died. But there had been an opportunity to prove whether he had or not.

Back in 2011 when Kassem visited the secret mortuary, he had not only photographed the body.

He had also managed to pull out some hair follicles, with a view to them being used in a DNA test. He had given them to senior officials in Berri’s office so they could have them analysed.

A match with a member of the Sadr family would prove beyond doubt whether the body was that of Musa sl-Sadr. However, Berri’s office never got back to Kassem.

Judge Hassan al-Shami, one of the officials appointed by Lebanon’s government to investigate Sadr’s disappearance, says Amal told him the follicle sample had been lost because of a “technical error”.

We presented our facial recognition results to Sadr’s son Sayyed Sadreddine Sadr. He brought senior Amal official Hajj Samih Haidous and Judge al-Shami to our meeting.

They all said they did not believe our findings.

Imam Sadr Foundation

Imam Sadr FoundationSadreddine said it was “evident” from the look of the body in the photo that it was not his father. He added that it also “contradicts the information we have after this date [2011, the year the photo was taken]”, that he is still alive, held in a Libyan jail.

The BBC has found no evidence to support this view.

But during our investigation it became clear to us that the belief Sadr is still alive holds great power as a unifying creed for many Lebanese Shia. Every 31 August, Amal marks the anniversary of his disappearance.

We repeatedly approached Berri’s office for an interview, and asked for comment on our findings. It did not reply.

The BBC also asked the Libyan authorities to comment on our investigation and to explain why the BBC team was seized by the Libyan intelligence service. We received no response.

Discover more from News Hub

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.