TenderCuts’ second innings: Lean stores, offline push, and focus on unit economics

The Chennai-based company currently operates 18 stores across Chennai, reporting an annual recurring revenue (ARR) of Rs 70 crore. The brand is on track to reach breakeven on a consolidated level in August 2025, with all its active stores hitting a positive EBITDA (earnings before net interest, income taxes, depreciation expense, and amortisation)—a rare feat in the challenging industry it operates in.

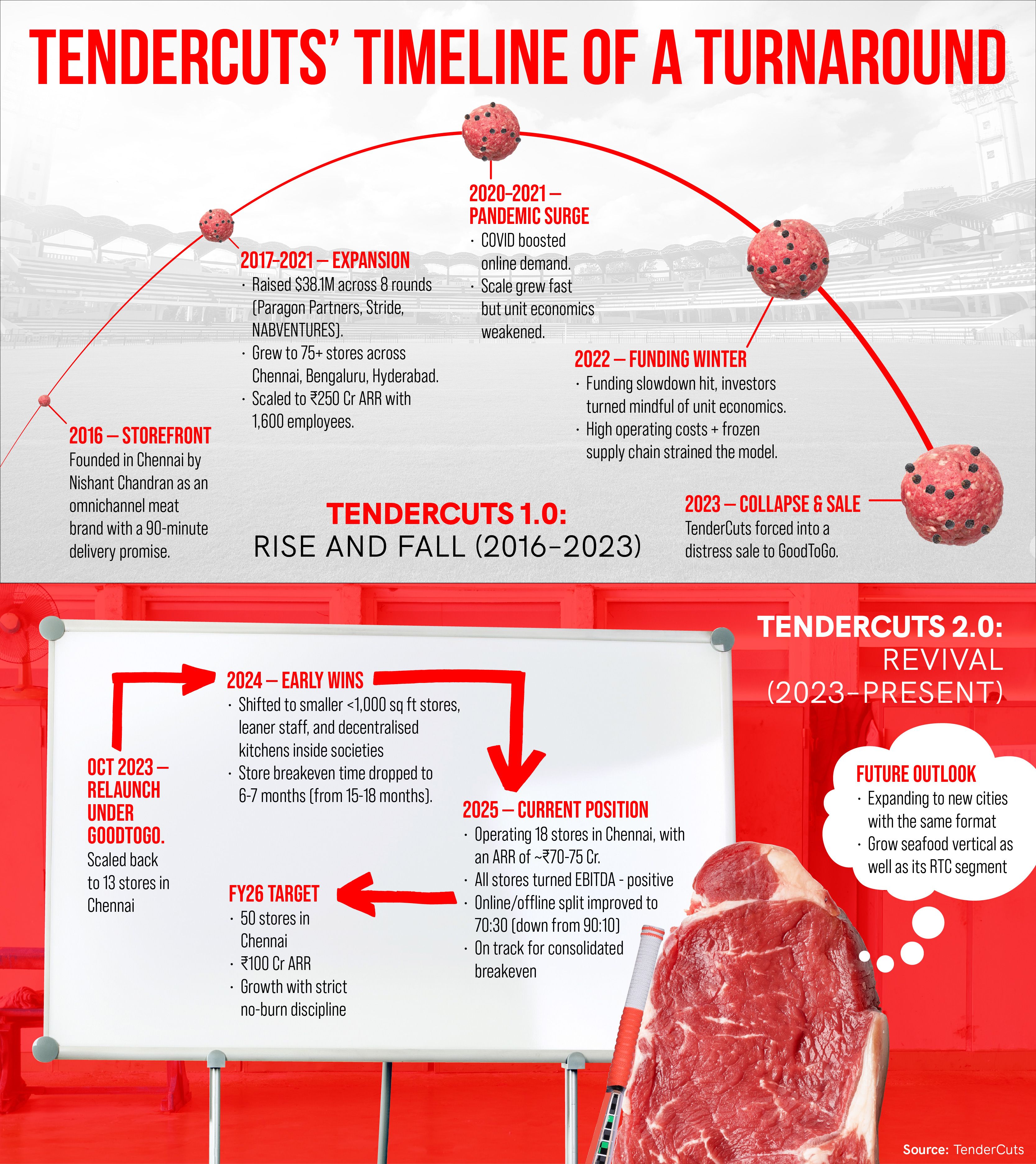

TenderCuts was acquired by Delhi-NCR-based meat startup GoodToGo in 2023 in a distress sale and has since surpassed its parent in terms of scale.

TenderCuts 1.0

TenderCuts was started in 2016 by Nishant Chandran as an on-demand omnichannel meat store with the promise to deliver an order within 90 minutes. The company tasted success relatively quickly, and at its peak in April 2022, TenderCuts had scaled to over 75 stores across Chennai, Hyderabad, and Bengaluru, with a 1,600-strong team driving the business to an ARR of Rs 240 crore.

Since September 2017, TenderCuts had raised a total of $38.1 million across eight rounds, according to Tracxn. It counted Paragon Partners, Stride Ventures, and NABVENTURES among its principal investors.

“They went on an expansion spree, opening a lot of stores in Bengaluru and Hyderabad. Originally from Chennai, they expanded cities purely to chase revenue after some investors indicated that if they doubled revenue, they would infuse additional capital,” notes Apoorva Sharma, Managing Partner at Stride Ventures, an investor in the combined entity.

However, when COVID-19 struck and presented online-first brands with a golden opportunity, the company realised it had overplayed its hand.

“We prioritised scale during the pandemic, and post COVID-19, and we could have done something better on the unit economics front while we were on the scale,” Sasikumar Kallanai, Co-founder of TenderCuts, tells YourStory.

However, after record capital inflow in 2021, the ecosystem was struck by a funding winter the next year as investors adopted a cautious approach, dealing a blow to the meat retailing industry.

“In 2022, the funding environment slowed down drastically. People were unable to raise money, and suddenly growth at all costs was no longer valued—profitability became more important than revenue growth,” adds Sharma.

The dearth of capital also exposed the complex operational requirements of the industry, including specialised cold-storage equipment, frozen foods supply chain, managing inventory, and juggling regulations which change as soon as one crosses the state border.

TenderCuts’ Chennai rival Fipola shut operations in 2023 after struggling to sustain high operational costs and low margins. Several other regional meat retail chains have either scaled back or exited, as investors have grown wary of the category’s capital intensity and operational complexities. Even the most visible players—like Licious and FreshToHome—continue to post heavy losses, reinforcing the perception that achieving profitability in this segment is hard work.

.thumbnailWrapper{

width:6.62rem !important;

}

.alsoReadTitleImage{

min-width: 81px !important;

min-height: 81px !important;

}

.alsoReadMainTitleText{

font-size: 14px !important;

line-height: 20px !important;

}

.alsoReadHeadText{

font-size: 24px !important;

line-height: 20px !important;

}

}

Industry major Licious clocked Rs 293.7 crore in losses in FY24, albeit 44% lower than the Rs 524 crore it clocked in the previous fiscal year. According to a report by Inc42, Chennai-based brand FreshToHome’s standalone net loss for its India operations stood at Rs 149.73 crore in the financial year 2023-24.

The sector also went through a heavy consolidation, with players like IPO-bound Zappfresh acquiring Mumbai-based Bonsaro and Bengaluru-based Dr. Meat between 2023 and 2024.

TenderCuts’ heavy expansion drive, the operationally complicated nature of the meat business, as well as an ill-timed funding winter, forced the company to shut shop and sell the brand to GoodToGo. GoodToGo was started in 2015 by two brothers, who leveraged the supply chain and connections of their family business to set up online meat delivery operations, along with selling through physical stores.

“Though we called ourselves an omnichannel brand, our positioning from inception till the restructuring was online-first, and we scaled to a greater strength. The biggest realisation through the journey of version 1 was that this category, even today, is a touch-and-feel category,” says Kallanai.

TenderCuts 2.0

Under its new masters, TenderCuts started cleaning up its act.

The startup revamped and optimised its offline presence to low-cost structures. It moved away from its high-street meat shop model to small neighbourhood kitchens, even establishing small stores inside large societies. It also moved away from large stores, with the store floor size now less than 1,000 sq ft.

Post-acquisition, TenderCuts tapped into GoodToGo’s operational backbone by centralising critical functions such as procurement, logistics planning, vendor negotiations, and certain administrative processes. This meant the brand no longer had to invest in separate teams or duplicate systems, freeing up capital and reducing overheads. Beyond cost savings, TenderCuts drew heavily from GoodToGo’s playbook, especially its offline-first strategy.

“GoodToGo has always been a profitable brand and had the view that smaller stores with more retail footprint were better than relying solely on online. In fact, GoodToGo’s revenue split is 80% offline and 20% online. While every region has its nuances, they were very clear that offline is very important, and you can’t rely only on online,” explains Stride’s Sharma.

TenderCuts still needed to trim the fat. It scaled down from 75 stores at its peak to just 13 neighbourhood stores across Chennai, operational since October 2023. The company made its processing stations smaller and also reduced the team size at these locations, running them frugally with fewer butchers.

“We scaled down on capital expenditures. Earlier, we were building at scale, and now we are building at one-third of that scale, at a unit economics-level store. So, from lean CAPEX to lean OPEX, and a store close to the customer, that is the real model we are after right now,” says Kallanai.

Its efforts began showing palpable returns quickly. Whereas earlier it took stores 15-18 months for a store to break even on an EBITDA level, the reworked model was hitting that milestone in just 6-7 months. The tighter store formats, leaner staffing, and neighbourhood-focused locations meant that each outlet reached profitability faster, reducing the drag of loss-making stores on the overall business.

Considering the nature of the industry, TenderCuts has also been steadily focusing on improving its supply chain, finding margins and efficiencies on every bite.

“In the earlier 1.0 model, we also built supply chain efficiencies, but it was more of a gradual journey that happened at a later stage. In this journey, with those prior learnings, we have been able to implement them from the very beginning, achieving a more efficient supply chain within a short period and continuing even at lower volumes,” the co-founder adds.

However, despite labelling itself as an offline-first brand, the majority of sales still come from its online channel, which allows users to place an order within a 4 km radius of a store. It relies on its last-mile fleet and D2C website channel to support operations.

At the time of restructuring, 90% of TenderCuts’ revenue came from online channels. That share has since dropped to about 70%, with offline contributing the remaining 30%—a shift the team views as only the first step.

“The aim is to move towards a 50:50 or even 60:40 offline-to-online split in due course,” says Sharma, noting that TenderCuts neighbourhood stores are steadily building a loyal walk-in base.

“The closer we are to the customer’s daily route, the more they choose us over a local butcher,” believes Kallanai, adding that the offline growth is a deliberate, long-term play.

The startup now plans to double down on its seafood offerings, which come with their own challenges, especially the seasonality of the catch, the need for cold storage transport from coast to cities, and the sheer variety.

“In terms of per capita consumption as a country, today, fish and seafood is the largest category, even more than chicken. But if you look across the market, even in your neighbourhood, you will not find many fish and seafood stores, which require a different skill set to process,” explains Kallanai.

It offers 250+ SKUs, including a variety of ready-to-cook options, marinated meats, and processed meats for consumers. The brand is targeting an annualised revenue run rate of Rs 100 crore by the end of FY26, up from the current Rs 75 crore. It plans to double its footprint to around 50 stores in Chennai over the next 24 months while keeping profitability intact.

Beyond its medium-term expansion plans, and if scale and profitability align, TenderCuts could also become an attractive acquisition target for legacy food and retail players looking to enter or consolidate in the fresh meat category.

Edited by Kanishk Singh

Discover more from News Hub

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.